Imagine a man with no boundaries or morals. He lies, cheats, fights, and argues, all in his own self-interest. He acts impulsively, and buzzsaws his way through anyone or anything that stands in his way. He blames everyone else for his problems, and takes no responsibility for his own actions. His allegiance is only to himself. Sound familiar?

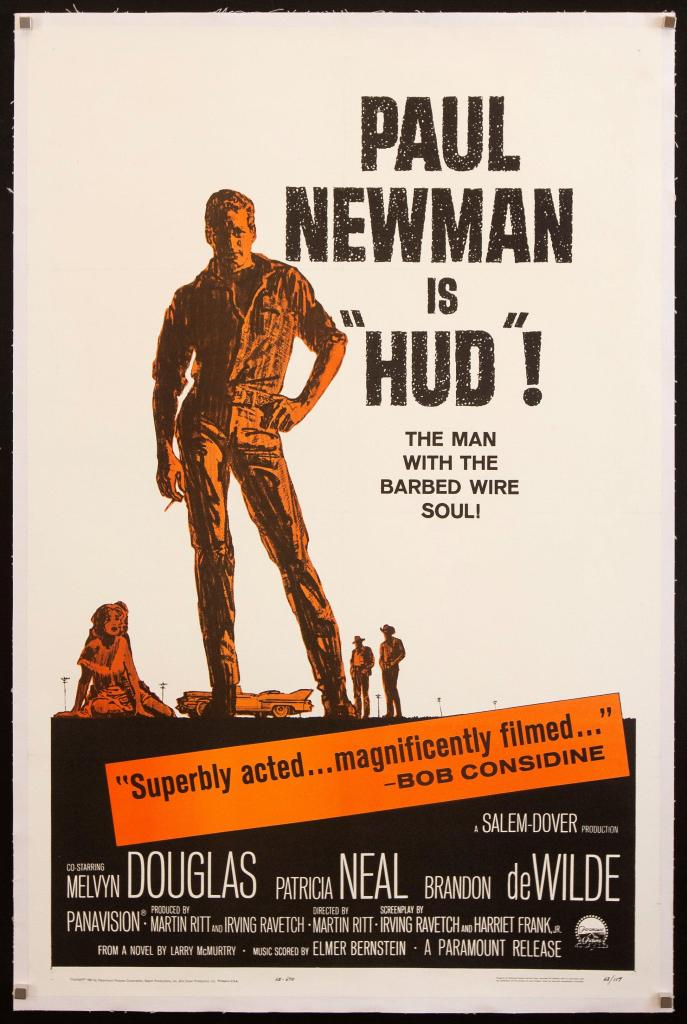

The man in question is the title character of the 1963 film, Hud, and he is a piece of work. He is played by Paul Newman, who gives a superstar performance full of swaggering malevolence. This was one of the defining roles of Newman’s early career, and it is easy to see why. He gets to do a little bit of everything here: lay on the charm, flash some sex appeal, flex his dramatic acting chops, and much more. In hindsight, he may have done too good a job. Not only was Newman’s performance iconic and influential for a couple of generations of moviegoers, but it also foreshadowed certain cultural changes in America’s national character much earlier than most people caught them.

But first, the plot: Hud belongs to a family of Texas cattle ranchers that is thrown into turmoil by an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease on their ranch. From there, it turns into an old school family battle of wills – between selfish and immoral Hud, and his ethical and upstanding father, Homer – over how best to address the outbreak. Caught in the middle is Hud’s nephew, Lonnie, who admires both Hud and Homer, and will eventually have to pick sides. Watching from the sidelines is the family’s wise, no-nonsense housekeeper, Alma, who serves as de facto referee, diplomat, and Greek chorus.

So, how much of a reprobate is Hud, really? Well, to start, he wants to sell the infected herd of cattle without disclosing that they are damaged goods. That way, he can make some money off of them instead of losing money by having to put them down. When Homer digs his heels in on that, Hud sues him. (Hud also calls his own father by his first name: who does that except a total louse?) He is also happy to sleep with anyone’s wife or start a bar brawl just for his own amusement. Most despicable of all, he eventually tries to have his way with Alma against her will, even though she may be the only person he actually likes. Liking people, however, has nothing to do with it because Hud is a man who acts completely on impulse. Whatever he wants, he tries to take it, and the consequences be damned. Let me put it this way: even Hud’s father does not like him, and says so right to his face in one of the film’s most memorable scenes.

Some background: Newman developed Hud with director Martin Ritt as a starring vehicle for himself. It is adapted from Larry McMurtry’s debut novel, Horseman, Pass By (which I have not read) by veteran screenwriting team Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr., and one big change they made in the transition from page to screen was a shift in protagonist. In the novel, Lonnie is the main character, whereas the title of the movie says it all. The switch is understandable for a couple of reasons. As presented in the film, Lonnie is mostly one-dimensional, a young innocent who is still becoming a fully-formed person. He is not as interesting as Hud, who is a full-blown SOB: hedonistic, unethical, unpredictable, and just the kind of flashy role that is typically catnip for an actor.

Newman and Ritt also chose to focus on Hud precisely because he is so vile. As film critic Shawn Levy explains in his excellent biography, Paul Newman: A Life, “…Hud’s unremitting cruelty was in part what recommended the material to Newman and Ritt: they wanted to make a movie that broke the mold of all the Hollywood films in which a leading man turned from heel to hero in the final reel…Ritt, Newman, and the Ravetches had intended an indictment of a certain strain in the American character…” So, Hud was intended to be a cautionary tale featuring the title character as an example of hubris run amok. Bookmark that little tidbit for now, and we will return to it in a minute.

The thematic slant of the film is brought to life perfectly by Ritt and veteran cinematographer James Wong Howe, who shoots in stark, unsentimental black and white. According to Levy, they chose that approach so “the film’s themes of corruption weren’t overcome by a romantic image of fading cowboy life.” Mission accomplished. The look of Hud enhances its emotional textures. The increasingly barren Texas landscape mirrors the surging desolation of Hud’s inner life. Standing in sharp contrast are the other characters, especially Homer, whose steadfast principles sometimes make him sound like too much of an old fogey, but Melvyn Douglas’ splendid performance humanizes him in three dimensions. Alma’s prosaic, world-weary earthiness is fleshed out perfectly by Patricia Neal’s superb performance. One gets the sense that she could be just as crude and vulgar as Hud (which may be one of the reasons he likes her), but she simply opted not to choose violence. Brandon deWilde’s performance as Lonnie is the perfect foil for Newman’s Hud, embodying the former’s innocence as an effective contrast to the latter’s impurity.

Then, there is Newman, who is magnificent here. His performance is perhaps best described by Levy as “a cross between Richard III and Elvis Presley.” He has star quality galore, and achieves the thematic goals of the film to powerful effect – perhaps too much so. When Hud opened to positive reviews in the spring of 1963, it also did strong business at the box office. The surprising part of that, at least for Newman and Ritt, was how much audiences liked the movie because they liked Hud. As Ritt later commented, “I got a lot of letters after that picture from kids saying Hud was right…The old man’s a jerk, and the kid’s a schmuck…The kids were very cynical; they were committed to their own appetites, and that was it. That’s why the film did the kind of business it did – kids loved Hud. That son of a bitch that I hated, they loved.”

In hindsight, it seems obvious why that happened. The filmmakers miscalculated their approach to the script by making the villain the main character. And, they did not realize that having someone as appealing as Newman playing such an asshole would maybe look like an endorsement of Hud’s behavior. As my friend John DeVore put it so brilliantly last year in an essay he wrote for Fatherly, “Being an asshole feels good, like scratching poison ivy blisters. Assholes can do whatever they want, whenever they want. To be an asshole is to be unshackled from concepts like honor, fair play and duty are hopelessly corny, old-fashioned goody-goody bunk…assholes swagger. They swash and buckle. They’re the new rock stars who give off pure, 100% IDGAF vibes.”

Today, we are all too familiar with the concept of the anti-hero protagonist (which is just a nicer way of calling the main character an asshole), but I imagine it was a more shocking phenomenon back in the 1960s. And, little did anyone know back then that Hud, the character, would be a harbinger of things to come in today’s political arena, which seems to be overrun with scorched earth clowns who drank some of his Kool-Aid. Because of that, Hud inspired more than a couple of earnest think pieces about how the past decade had confirmed the film’s sociological prescience.

Like other works of art, Hud has shown us that it can be about more than one thing, and its competing interpretations – both the repudiation of Hud, and the endorsement of him – are both equally discernible today. And, it is such an expertly made film that it can withstand whatever the audience wants to project onto it or take away from it. But, its original intent is plain as day when Homer issues this warning to Lonnie: “Little by little the look of the country changes because of the men we admire…You’re just going to have to make up your own mind one day about what’s right and wrong.”