The concept of the perfect album side is not a new one. I was first introduced to it by the radio station of my youth: 102.7 WNEW-FM, billed as “the place were rock lives.” Mondays through Fridays at midnight, they would play a different album side by listener request (this was back in the days when albums had actual sides). It was such a fun, cool way to learn about rock music in a way that allowed for a deeper dive into a given artist’s work, one that covered more than just their well-known hits (although there were still plenty of those to go around). This was how I got introduced to a slew of back catalogue surprises, weird curiosities, and some new favorites, sometimes all within the same week.

The midnight Perfect Album Side was one of my favorite features on WNEW, so I’m reviving it here as Strictly Back Catalogue‘s leadoff recurring column.

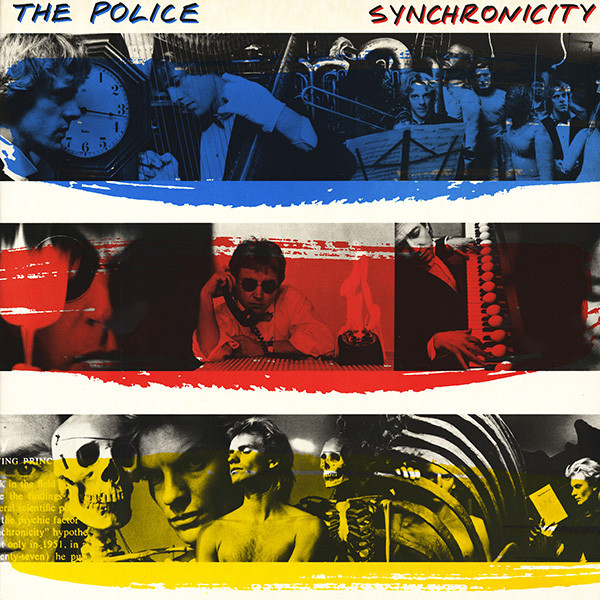

First up: side two of The Police’s classic 1983 album, Synchronicity. In my view, this is a great example of a perfect album side. It has thematic and tonal consistency, exemplary songwriting, and strong musicianship. There are catchy hooks galore here – all the more impressive since it may also be one of the most dour and idiosyncratic albums to ever go multi-platinum. The Police faced multiple obstacles during recording: Sting’s first marriage had just fallen apart, tensions within the band had reached a breaking point (and, sure enough, they broke up for good after an 8-month world tour), and they chose some puzzling sources of inspiration for the album: Arthur Koestler’s book about parapsychology, The Roots of Coincidence, and Carl Jung’s theory of synchronicity. Not your typical pop music jumping-off points.

And yet, The Police managed to create a striking, powerful, hypnotic work out of disparate elements that would have usually bored a lecture hall full of college freshman and ended more than a few friendships, respectively. Synchronicity‘s best qualities are on full display on side two. Check it:

“Every Breath You Take”

Robert Christgau called this one “the single of the summer,” which it was: it spent eight consecutive weeks at No. 1 on the U.S. Top 40 in the middle of Thriller-mania, which was no small feat. In his book The Heart of Rock & Soul: The 1,001 Greatest Singles Ever Made, Dave Marsh wrote that “Every Breath You Take” announces itself as a classic from the get-go (which could be said about this entire album). It works as both political allegory and a treatise on romantic and sexual obsession. Marsh initially heard the song as the former, even though it was inspired by more personal events: the aforementioned dissolution of Sting’s marriage. (In hindsight, though, Sting has come to agree more with Marsh’s interpretation.) However one hears it, “Every Breath You Take” remains a haunting, enduring work, a standout of The Police’s catalogue and a compositional high point for Sting.

“King of Pain”

Another haunting track that went Top 10 (peak position: No. 3 on the U.S. Top 40). The lyrics make more sense within the context of Sting’s volatile emotional state at the time, but it’s the feeling and the sound of “King of Pain” that carries it: the reverb on Stewart Copeland’s drums, the minor key piano opening coupled with Andy Summers’ janky guitar pluckings, the song’s upbeat final chorus in which Sting joyously declares “I will always be king of pain!” A broody, contemplative miracle from start to finish.

“Wrapped Around Your Finger”

Yet another pensive earworm, but also another Top 10 hit for the band (peak position: No. 8 on the U.S. Top 40). This is the one where Sting works out the power dynamics of the song’s vindictive apprentice finally one-upping his master (he called it a “spiteful song about turning the tables on someone who had been in charge” in a 1985 interview for the now-defunct Musician magazine). Once again, though, the strength is in the atmospherics: Andy Summers’ distant, echoey guitar part moves through the song like a snake, and Sting’s melody is one of the most tenacious he’s ever written.

“Tea in the Sahara”

This is the real sneak preview of what Sting’s soon-to-be solo career would be like: earnest and a little self-important, but sonically and musically ambitious. Despite this song’s literary origins (it’s inspired by a Paul Bowles novel), it feels like a cool breeze that provides respite from the thick melancholy on the rest of the side. It’s airy and has a bit of grand, cinematic sweep, but is also a deeply weird find on a hit album that sold over 8 million copies worldwide. But, then again, that’s how good The Police were: they could get away with a track like this on the biggest album of their career.

“Murder by Numbers”

A true bonus track: it was only originally available on the cassette release, not the vinyl LP. I had the vinyl version growing up, and consequently didn’t hear this track until years later. I never sought it out because, for me, side two of Synchronicity was already perfect as it was. But, this song does add a little kick, and is more of a proper final track. One can hear the band’s jazz chops more obviously, and they sound more relaxed here than at any other point on the album. It’s up to the listener to decide which of the final two songs is the actual closer.